Statins Should be Removed from the Market! - Part 2

- Dr. Thomas J. Lewis

- Feb 10, 2024

- 11 min read

I'm not the only one who feels this way. Maryanne Demasi, PhD is an investigative journalist who writes for online media and top-tier medical journals. She was a TV presenter for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) for over a decade. Her articles are hard-hitting and always on point.

Question? Would you take an antibiotic for life?

Please answer.....

Then read this. Notice, I did NOT use the term antibiotic. That term is "forbidden "wrt statins - but what is an antimicrobial? It is an antibiotic. Note there are only 6,000+ articles.

Here is one that probably aggravated Harvard and Ridker.

If you are on a statin, the only reason they provide some benefit in limited groups of people is because they are antibiotics and crestor is NOT one of the stronger ones.

YOU HAVE BEEN DUPED (AGAIN) BY BIG PHARMA!

LEWIS: I met Ridker around 2010 as he had an office in the same building as my mentor, Dr. Trempe. The Jupiter trial was actually intended to show that Crestor could reduce CRP - the key marker of vascular inflammation.

One of Dr. Trempe's patients was an epidemiologist on the Jupiter trial. Dr. Trempe ran CRP on her as he did on everyone for over 30 years. Her CRP was elevated - my recollection is that the value was around 8 mg/dL, whereas you want your CRP to be well <1.

According to Dr. Trempe's recollection, this lady returned to Dr. Ridker and said something like, "Dr. Ridker, my CRP is "8" - what am I to do?"

Dr. Ridker's response: "Get used to it. Sh** happens."

So much for the author of the CRP reduction trial and Crestor!

Here is Dr. Demasi' Part 2 on why statins should be removed from the market.

Crestor® (generic name rosuvastatin) was initially approved in 2003 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of high cholesterol.

But the manufacturer AstraZeneca, had yet to prove that its drug could do more than just lower cholesterol. It also had to show that rosuvastatin could reduce heart attacks and strokes like its competitors.

Rosuvastatin was put through its paces in a series of randomised controlled trials - CORONA, GISSI-HF and AURORA - but all three failed to demonstrate a benefit in clinical outcomes for various patient populations.

So all hopes were on the JUPITER trial -- could rosuvastatin reduce heart attacks in apparently healthy people with normal cholesterol levels and no evidence of prior heart disease (known as primary prevention)?

Trial participants were also selected for having raised levels of C-Reactive Protein (CRP), believed to be a marker of inflammation.

The trial would turn out to be one of the most controversial studies of its time.

A miracle?

After only 1.9 years into the JUPITER trial, AstraZeneca made the shock announcement that the trial would be terminated prematurely.

Originally planned to last 4yrs, the trial was stopped early by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board because the drug’s benefits appeared to be so spectacular, that they considered it unethical to withhold rosuvastatin therapy from people on the placebo.

No data had been disclosed in a medical journal at this point but they said they’d obtained “unequivocal evidence of a reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality amongst patients who received CRESTOR when compared to placebo.”

It took seven months for the details to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine along with a press release boasting that 20 mg of rosuvastatin daily could cut the risk of heart attacks by 54%, p<0.001 and strokes by 48% (p=0.002).

It was a staggering reduction, unmatched by any other statin on the market.

The cardiology community celebrated, commentators called it “miraculous,” and a media frenzy ensued. News headlines encouraged people to “eat” their statins to avoid a heart attack.

“It’s a breathtaking study. It’s a blockbuster. It’s absolutely paradigm-shifting,” said Steven Nissen, a cardiologist at Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

Quote from "Person of Interest" TV series. "The higher up you go, the more difficult it becomes to tell the good guys from the bad guys."

“This takes prevention to a whole new level,” said Douglas Weaver, then-president of the American College of Cardiology. “Yesterday you would not have used a statin for a patient whose cholesterol was normal. Today you will.”

Within months, the FDA extended the licence of rosuvastatin to include the indication of reducing major cardiovascular events in primary prevention, thereby increasing its use in men over 50 and women over 60.

It meant that ~80% of the middle-aged to elderly population in the US would be eligible for rosuvastatin.

Critics rise up

Independent researchers (De-Lorgeril, Lopez, and Morrissey) closely examined the data from the JUPITER trial and highlighted some major concerns over the interpretation and veracity of the data.

First, terminating a trial prematurely (after a median of only 1.9 years) is well-known to skew the outcomes of that trial to favour the benefits of the drug and under-estimate the harms.

Second, data showed that rosuvastatin reduced cardiovascular events (combination of heart attack, stroke and cardiovascular death) by 47% - a relative risk reduction. But the absolute risk reduction was minuscule - 0.83% (1.75% statin vs 0.93% placebo).

It meant that 120 people needed to be treated with 20 mg of rosuvastatin daily to prevent one cardiovascular event - hence, 119 of those people would not benefit.

Third, rosuvastatin increased the proportion of people who developed high blood sugar levels and new onset diabetes compared to those taking placebo (diabetes being a major risk factor for heart disease).

A re-analysis of the data found that if 1000 people took rosuvastatin daily for two years, you could prevent 8 of those people from having a heart attack or stroke, but 6 of them would develop diabetes.

Fourth, rosuvastatin did not reduce the risk of cardiovascular death (fatal heart attacks or fatal strokes), which is a major red flag for a drug that claims to have “dramatic” cardiovascular benefits.

In fact, it was not even addressed by the JUPITER authors in the journal article. They buried the data within a table which had to be calculated manually by the reader.

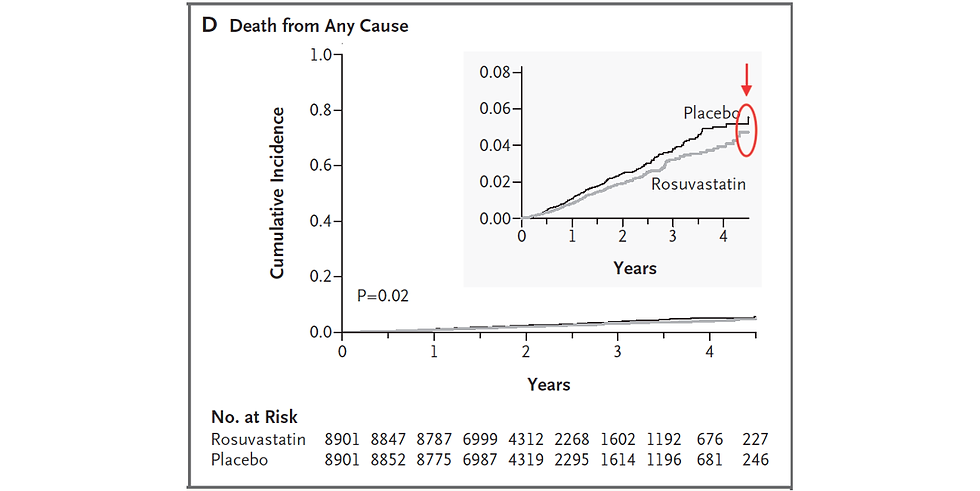

Fifth, the study found that rosuvastatin reduced all-cause mortality by 20% (relative risk reduction). The absolute risk reduction was 0.6%.

It was a remarkable feat since a meta-analysis of 11 randomised controlled trials involving 65,229 participants found no evidence for the benefit of statin therapy on all-cause mortality in high-risk primary prevention.

In the JUPITER trial, critics pointed out that while the rosuvastatin and placebo groups diverged at one point (black and grey lines in graph), they seemed to be converging towards the end of the study period (see red highlight).

LEWIS - REMEMBER - ANY EFFECT IS DUE TO STATIN'S ANTIBIOTIC PROPERTIES - NO LIPID LOWERING / DIABETES CAUSING. CAUSING DIABETES AND CAUSING HEART DISEASE GO TOGETHER.

Some skeptics thought it might’ve been the real reason why the trial was terminated early, i.e. to avoid the two groups overlapping and erasing the all-cause mortality benefit.

Even the FDA was not convinced by the data - in a brief, the agency’s own statistician wrote:

Further inspection of the data shows that the Kaplan-Meier curves converge toward the end of the trial. …. Thus, it is not clear whether or not rosuvastatin confers a total mortality advantage compared to placebo even though the logrank test appears to detect the separation of the survival curves up to over 4 years.

Lastly, critics raised concerns about the extent of the conflicts of interest of the JUPITER authors, saying that their disclosures revealed an unacceptable degree of commercial bias.

Not only was the study funded by AstraZeneca, but 9 of 14 authors had accepted money from the drug maker. Also, the lead author on the study, Dr Paul Ridker of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, held the legal patent on the CRP testing used to select participants for the trial.

LEWIS - I CALL THIS DUDE THE LITTLE HITLER, MENGELE, OR FAUCI OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE.

Is it time to ban rosuvastatin?

The simple answer is ‘yes’ said Sidney Wolfe, who was a drug safety expert and co-founded Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, a patient advocacy group.

Prior to his passing, Wolfe spent years raising serious concerns about the safety of rosuvastatin, even before the drug was licensed by the FDA in 2003.

Sidney Wolfe, physician and co-founded of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group

When I spoke with Wolfe last year, he said his opinion of rosuvastatin had not waivered.

“Look, studies have continued to show that rosuvastatin should be pulled off the market in my view,” said Wolfe. “If a drug has no unique clinical benefit, but unique harms, it should not be approved. From the pre-approval evidence to its current evidence, both are true of rosuvastatin.”

Wolfe pointed to a recent observational study published in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, and funded by National Institutes of Health.

The study found that new users of rosuvastatin experienced an increased risk of haematuria, proteinuria and kidney failure compared to new users of atorvastatin, the other high-intensity statin on the market.

“These latest data only reinforce my view that rosuvastatin is not a safe drug, it continues to show up the same problems it did years ago and therefore, should not be on the market," said Wolfe.

Until recently, Wolfe ran a monthly newsletter called “Worst Pills, Best Pills.” The publication gives expert opinions on more than 1,800 medicines and supplements.

He said that over the last five decades, his organisation had petitioned the FDA about 50 to 60 drugs of concern -- 40 of which, he said proudly, have now been withdrawn from the market or have restricted use.

Wolfe said the manner in which rosuvastatin was sold to clinicians, the FDA, and the public was deceptive -- in his most recent review of the drug, Wolfe made an unequivocal ruling -- “Do not use this drug.”

Here is part 1.

I subscribe to her paid substack and recommend you consider doing the same to support her investigative work. Here is an example.

The cholesterol-lowering drug Crestor® (generic name rosuvastatin) was the last of seven statins in the drug class to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), paving the way for other regulators to follow the lead.

With the help of an aggressive marketing campaign, the cholesterol-busting drug quickly rose to prominence in an already crowded market.

In Australia for example, rosuvastatin is now the most prescribed drug, with over 14 million prescriptions written in the 2020/2021 financial year. Its competitor, atorvastatin, is a close second.

No wonder Australians, a population I considered very independent-minded, rolled over and took the jab in unprecedented numbers. Statins harm the brain, thus impacting rational thought.

Early safety issues overlooked

Early testing showed that rosuvastatin was the most potent of all statins (milligram for milligram) at lowering cholesterol. But its higher potency meant greater toxicity.

Even before the FDA approved rosuvastatin, the drug was dogged by safety concerns after trial participants reported developing kidney problems and a rapid muscle-wasting condition called rhabdomyolysis.

In 2003, the FDA presented these findings to its advisory panel - specifically demonstrating rosuvastatin led to dose-dependent increases in proteinuria (abnormal levels of protein in the urine) and haematuria (blood in the urine).

The FDA also presented seven cases of rhabdomyolysis - a potentially fatal condition - which developed approximately nine months after subjects began taking 80 mg of rosuvastatin.

This was especially concerning because it was the only statin in the drug class that caused rhabdomyolysis in trial participants before its approval.

Not even cerivastatin, which was eventually banned in 2001 after 52 people died from rhabdomyolysis, had any cases that showed up in the clinical trials before its approval.

After deliberation, the FDA dismissed the concerns, saying that the rhabdomyolysis cases occurred mainly in patients taking the highest dose of rosuvastatin (80 mg), prompting the decision to discontinue manufacturing the higher dose.

In the end, the FDA went ahead and approved rosuvastatin at doses between 5 and 40 mg for the treatment of “primary hyperlipidemia” (elevated lipid levels).

Marketing hype

Once approved, the drug manufacturer - AstraZeneca - wasted no time boasting to investors that it would spend over a billion US dollars promoting Crestor® in order to dwarf its competition.

The undisputed market leader then was Lipitor® (Pfizer), with estimated sales of US$7.4 billion in 2002 and commanding a 42% market share in the statin drug class.

AstraZeneca’s then-CEO Tom McKillop vowed to knock Pfizer’s Lipitor out of its top spot, saying he would do whatever it took to persuade doctors to prescribe rosuvastatin.

“We’ve got to drive the momentum…you get one shot at launching a major new product. This is our shot,” he remarked.

It prompted Richard Horton, editor-in-chief of The Lancet to write a scathing editorial demanding that McKillop desist from his “unprincipled campaign.”

Horton labeled it “blatant marketing dressed up as research,” urging physicians to “tell their patients the truth” about rosuvastatin’s inferior evidence base (at the time, the drug had not been shown to reduce heart attacks, only lipid levels).

But McKillop responded by saying that it was “unthinkable” that AstraZeneca would desist from its efforts to make the drug more widely available to the public.

“I deplore the fact that a respected scientific journal, such as The Lancet, should make such an outrageous critique of a serious, well-studied, and important medicine,” wrote McKillop at the time.

Determined to usurp the statin market, AstraZeneca launched a series of print and TV direct-to-consumer advertisements.

However, the marketing campaign made several false and misleading claims about the drug and caught the regulator's attention.

A TV ad, for example, falsely claimed that rosuvastatin (Crestor) was superior to its biggest competitor, atorvastatin (Lipitor). So, the FDA sent a warning letter to AstraZeneca stating;

The superiority claim was based on a study funded by AstraZeneca, which compared Crestor against other statins in that drug class – while Crestor performed better, it was not statistically significant. Accordingly, your suggestion that Crestor is superior to Lipitor is therefore misleading.

AstraZeneca pulled the ads, but the message had already been widely disseminated.

Post-marketing surveillance

After only seven months on the market, the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) recorded 18 cases of rhabdomyolysis.

Despite previous assurances by the FDA that rhabdomyolysis cases were confined to the 80 mg dose (which was discontinued), the cases reported to FAERS occurred in people taking much lower doses of rosuvastatin, i.e., 10 to 20mg.

There were also eight reported cases of acute renal failure and four of renal insufficiency in patients on rosuvastatin – again, mostly occurring at the lower dose of 10mg.

Sidney Wolfe, co-founder of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, petitioned the FDA to ban Crestor after raising concerns about the rhabdomyolysis cases in the population.

However, the FDA denied the petition and blamed the higher rates of reported rhabdomyolysis on the negative media publicity over the withdrawal of cerivastatin (which led to 52 deaths).

“This is absurd,” said Wolfe in a statement then.

Wolfe’s own analysis showed the rate of rhabdomyolysis with rosuvastatin was 6.2 times higher than all statins combined -- and those cases were reported between Oct 2003 – Sept 2004, a time when the reporting of all statins would’ve been affected by the negative media publicity over cerivastatin.

“Once again, when faced with concerns about a drug's safety, the FDA has sided with the drug company AstraZeneca instead of the public….this will represent yet another blow to the agency’s badly tarnished reputation,” said Wolfe.

AstraZeneca - impervious to the criticism - marched ahead and commenced a major clinical trial of rosuvastatin, hoping to show that the drug could reduce cholesterol and heart attacks.

The trial would turn out to be the most controversial study of its time - The JUPITER trial.

Lewis Comment: I know the author of the JUPITER trial - Paul Ridker. You might be interested to know that the trial was designed to show that rosuvastatin (Crestor) reduced inflammation as measured by CRP. Ridker is chair professor of epidemiology at Harvard Medical School at Brigham and Women's Hospital, and he occupied the same building as Dr. Trempe, my mentor. Unsurprisingly, "The Brigham" is named on both the Crestor and CRP patents.

Am I implying a conflict of interest? YES.

Weekly Webinar Links: Join us for detailed health information - at no charge. All are welcome.

Monday at noon EST -

Wednesday at 8 pm EST -

Be Bold - Be Brave - Stay Well

Comments